Imagine this: when you flip through a photo album and see pictures of past family trips, do you want to revisit those places and relive those warm moments? When browsing an online museum, do you want to freely adjust your perspective, observe the details of the exhibits up close, and enjoy a full interaction with the cultural relics? When doctors face patients, can they significantly improve diagnostic accuracy and efficiency by synthesizing a 3D perspective of the affected area based on images and providing estimates of lesion size and volume?

NeRF (Neural Radiance Field) technology is the key to making these things a reality. It can reconstruct the 3D representation of a scene from multi-angle captured images and generate images of the scene from any viewpoint and position (new viewpoint synthesis).

The following video demonstrates how NeRF technology is used to achieve 3D roaming by capturing some static images of Taichi offices with a mobile phone:

In the past two years, NeRF technology has become a hot field in computer vision. Since the groundbreaking work of Mildenhall et al. in 2020, NeRF: Representing Scenes as Neural Radiance Fields for View Synthesis, the NeRF field has spawned many subsequent studies, especially the recent improved work Instant NGP, which was listed as one of Time Magazine's Best Inventions of 2022.

Compared with previous research, the significant breakthroughs achieved by the mentioned NeRF and Instant NGP papers are:

- NeRF can obtain a high-precision representation of the scene, and the images rendered from new angles are very realistic.

- Based on NeRF's work, Instant NGP significantly shortens training and rendering time, reducing training time to within a minute, and making real-time rendering easily achievable. These improvements make NeRF technology truly feasible for implementation.

Not only researchers in the field of deep learning, but also professionals in many other industries are closely following the progress of NeRF, thinking about the possibilities of applying NeRF in their fields.

The main purpose of this article is twofold:

- We want to introduce how Taichi and PyTorch can be combined to create a fully Python-based Instant NGP development workflow. Without a single line of CUDA code, Taichi will automatically calculate the derivatives of your kernel and achieve similar performance as CUDA. This allows you to spend more time on research idea iterations than tedious CUDA programming and performance tuning.

- Mobile devices will be an essential scenario for NeRF implementation in the future. We introduce the use of Taichi AOT (ahead-of-time compilation) framework, which can deploy the trained NeRF model on mobile devices without worrying about platform compatibility. The following animation demonstrates our efforts using Taichi's AOT framework to port the Lego model from the Instant NGP paper to an iPad for real-time inference and rendering:

We will first briefly review the principles of NeRF and the improvements of Instant NGP, and then introduce the combination of Taichi and Instant NGP.

Part I: What is a Neural Radiance Field (NeRF)

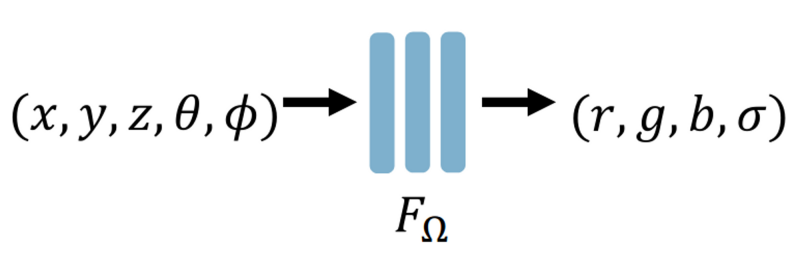

In simple terms, a neural radiance field is the encoding of an entire 3D scene into the parameters of a neural network. To render a scene from any new viewpoint, the neural network needs to learn the RGB color and volume density σ (i.e., whether the point is "occupied" or not) of each point in space. The volume density at a point is independent of the viewpoint, but the color changes with the viewpoint (e.g., the object seen from a different angle changes), so the neural network actually needs to learn the color (r, g, b) and volume density σ of a point (x, y, z) under different camera angles (θ, φ) (i.e., latitude and longitude).

Therefore, the input to the neural radiance field is a five-dimensional vector (x, y, z, θ, φ), and the output is a four-dimensional vector (r, g, b, σ):

Assuming we have such a neural radiance field, sending the corresponding (r, g, b, σ) of each point in space further into volume rendering will result in a 2D image seen from the current viewpoint (θ, φ).

The concept of volume density (volume rendering) is often used in computer graphics for rendering media such as clouds and smoke. It represents the probability that a point will block a ray of light as it passes through it. Volume density measures the contribution of a point to the final color of the ray.

Volume Rendering

The core step of NeRF is a processed called volume rendering. Volume rendering can "flatten" the neural field into a 2D image, which will then be compared with a reference image to generate loss. This process is differentiable, so it can be used to train the network!

Before introducing volume rendering, let's first understand the basic principles of camera imaging. In computer graphics, to save computational resources, it is assumed that the color of a point in the scene after being hit by a ray emitted from the camera is the color of the pixel at the intersection of the ray and the screen:

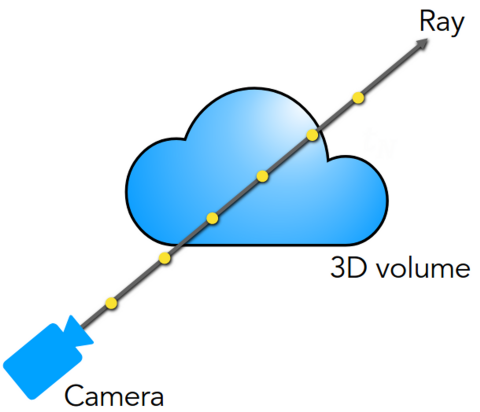

However, when rendering atmospheric, smoke-like media, rays pass through the media rather than stopping only at the surface of the media. Moreover, during the rays' propagation, a certain proportion of the rays will be absorbed by the media (not considering scattering and self-emission). The portion of the media that absorbs the rays contributes to the final color of the rays. The higher the volume density, the more rays are absorbed, and the more intense the color of this part of the media. So the final color of the rays is the integral of the colors of the points along the path.

Assuming the camera is at o and the ray direction is d, the equation of the ray is r(t)=o+t*d, and its predicted pixel color c(r) is

In the formula, T(t) represents the proportion of light transmitted to point t, and σ(t)dt represents the proportion of light blocked by a small neighborhood near point t. The product of the two is the proportion of light reaching t and being blocked at t, multiplied by the color c(r(t), d) of that point, which is the contribution of this point to the final color of the ray. The integral interval [t_n, t_f] represents the nearest intersection point t_{near} and the farthest intersection point t_{far} of the ray with the medium.

In actual calculations, we need to use discrete sums to approximate the integral value. That is, we sample certain discrete points along the ray and weight their colors by summing them up. We won't go into details of this discretization process, but you can check out explanations like the one in the image link above.

NeRF Training

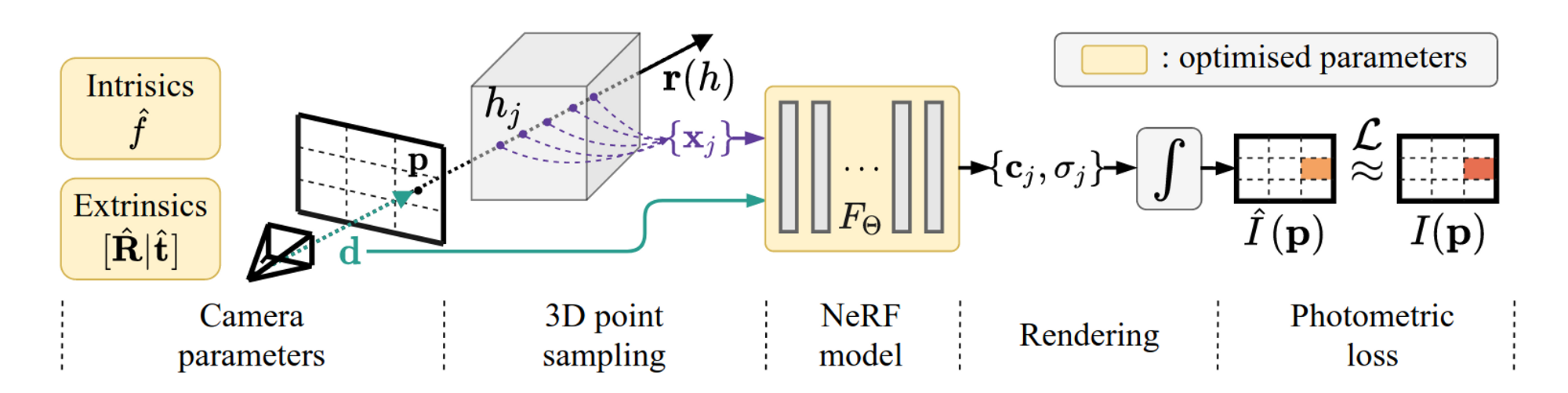

With the knowledge of neural radiance fields and volume rendering, let's further look into the training process of NeRF. The entire process is divided into five steps, as shown in the following figure:

- [Camera parameters] After preparing a set of captured 2D images, the first step is to compute the camera pose parameters for each image. This can be done using existing tools like COLMAP. COLMAP matches common points in the scene appearing in different images to compute the camera pose. In addition, we assume that the entire scene is located within a cubic box with a range of

[-1,1]^3. - [3D point sampling] For a real image, a ray is emitted from the camera, passing through the image and entering the scene. The pixel value

I(p)of the intersection pointpbetween the ray and the image is the reference color. We discretely sample several points along this ray. The spatial coordinates(x, y, z)of these sample points and the camera poseθ, φcomputed in the first step are combined as the input to the neural network. - [NeRF model] Predict the color and density of each sample point on the ray through the neural network.

- [Rendering] Through volume rendering, we can use the color and density of the sample points output by the neural network in the previous step to compute the discrete sum, approximating the pixel value

\hat{I}(p)corresponding to the ray. - [Photometric loss] By comparing

\hat{I}(p)with the true color valueI(p)of the ray and calculating the error and gradient, the neural network can be trained.

Improvements of Instant NGP

The original version of NeRF has already produced impressive results, but its training speed is relatively slow, usually taking one to two days. The main reason is that the neural network used in NeRF is a bit "large". In 2022, NVIDIA's paper Instant NGP significantly improved this aspect. The core improvement of Instant NGP compared to NeRF is the adoption of a "Multi-resolution Hash Encoding" data structure. You can understand that Instant NGP replaces most of the parameters in the original NeRF neural network with a much smaller neural network while additionally training a set of encoding parameters (feature vectors). These encoding parameters are stored on the vertices of the grid, and there are a total of L layers of such grids, which are used to learn the details of the scene at different levels from low to high resolution. During each training, the parameters of the small neural network and the encoding parameters in the 8 vertices around point (x, y, z) on each layer of the grid will be updated.

Another important engineering optimization of Instant NGP is to implement the entire network in a single CUDA kernel (Fully-fused MLP), so that all computations of the network are performed in the GPU's local cache. According to the paper, this results in a 10x efficiency improvement.

Part II: Training Instant NGP with Taichi

The NGP project is open-sourced. The project is written in CUDA and carefully optimized for all core components, making it very fast. However, using CUDA usually accompanies manually managing memory and hand-written parallel computing code for derivatives, which is very painful and error-prone.

There are also community-contributed PyTorch-based implementations, but the pure PyTorch version is significantly lower than the CUDA implementation. Although PyTorch is well-optimized for networks like MLP, it is less efficient for the hash encoding and volume rendering parts. For operations like interpolation and ray sampling, PyTorch launches many small kernels, resulting in very low efficiency.

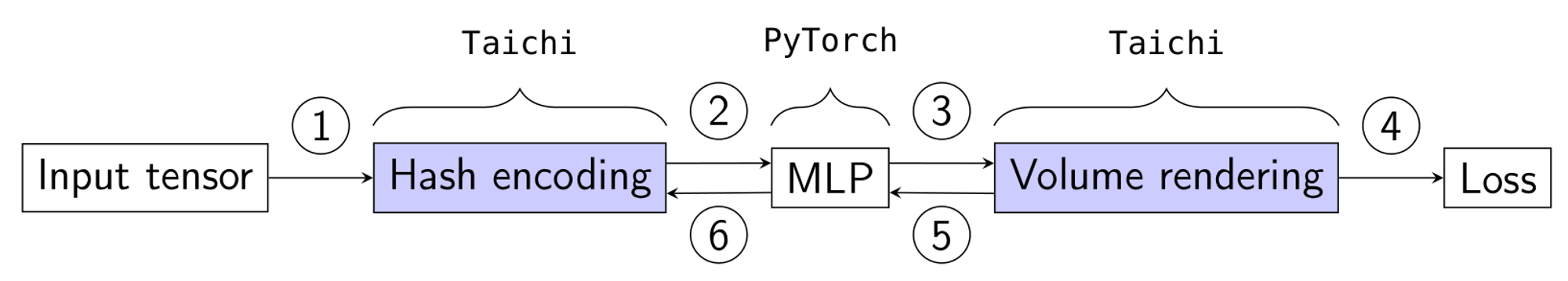

Is there a way to achieve CUDA-like runtime efficiency without writing CUDA and only writing Python? Of course! You can combine Taichi and PyTorch: use PyTorch for the MLP inference and training parts while writing the hash encoding and volume rendering parts with Taichi. The workflow is shown in the following diagram:

As shown in the diagram, we replace the hash encoding and volume rendering computations that PyTorch is not good at with corresponding Taichi kernels while retaining the PyTorch inference and training network parts. Taichi and PyTorch can conveniently and efficiently exchange data between each other, allowing users to easily organize Taichi and PyTorch code in a modular manner and conveniently modify or replace modules.

Note: We also implemented a completely Taichi-based Instant NGP, so that we don't depend on PyTorch for mobile deployment

Unlike PyTorch, Taichi adopts a SIMT programming model similar to CUDA, encapsulating all computations in a single kernel as much as possible. Therefore, Taichi can achieve efficiency close to CUDA.

Moreover, Taichi supports automatic differentiation (Autodiff), significantly improving development efficiency and ensuring gradient accuracy, eliminating the need for a large amount of manual gradient derivation work.

The Taichi NeRF Github repository is here: https://github.com/taichi-dev/taichi-nerfs. Try it out!

The efficiency of the Taichi implementation of Instant NGP is very close to the efficiency of the original CUDA implementation provided by the author. According to our tests, the training part of Taichi is only about 20% slower, and the inference part has almost no difference. As shown in the table below:

| Training Time | CUDA | Taichi |

|---|---|---|

| Instant NGP | 170s | 208s |

- Lego model with 800x800 resolution, trained for 20,000 iterations, tested on a machine running Ubuntu 20.04 with a single RTX 3090 GPU.

- For detailed training method, please refer to: https://github.com/taichi-dev/taichi-nerfs#train-with-preprocessed-datasets

Fast model iteration using Taichi

In addition to not having to write CUDA code manually, another advantage of developing NeRF with Taichi is the ability to quickly iterate on the model code. Here, we want to share an example of making targeted modifications to the Instant NGP model during the development of mobile deployment.

In our early attempts, we tried to extract the inference part from the Taichi NeRF training code and deploy it directly to a mobile device, only to achieve a dismal performance of 1 fps. The main performance bottleneck lies in the highly random access to data in the hash encoding part of Instant NGP. This is not an issue in CUDA where the cache can hold all hash tables, but mobile devices suffer this due to insufficient cache, resulting in low performance.

We expect that data reads and writes are done in a continuous manner, which requires tightly packed memory layout. Therefore, we replaced the hash table with compact grid structure, significantly improving the throughput of memory access. This code modification required less than 30 lines. Combined with other optimization methods, we finally achieved real-time interaction with over 20 fps on mobile devices.

Part III: Deploying Taichi-NGP on mobile devices with Taichi AOT

Performing NeRF inference on mobile devices has two challenges. First, invoking mobile GPU resources for neural network computations requires manual writing of corresponding shader code, which is both complex and difficult to debug. Second, the limited hardware resources on mobile devices often struggle to support the relatively complex computations of NeRF. The Taichi AOT deployment framework can address both pain points, allowing us to easily run the trained Taichi Instant NGP model on mobile devices.

An alternative approach is to place NeRF inference on the cloud and transmit images back to the mobile device for display. Compared to purely offline inference, this method is not only limited by network constraints but also has higher costs due to the inability to leverage mobile computing resources, resulting in limited application scenarios.

Taichi AOT is a deployment solution that accompanies the Taichi programming language. It allows you to compile the same Taichi code to mobile device backends like Vulkan, Metal, and OpenGL with a single click, and provides a unified C-API for easy invocation, greatly reducing the difficulty of mobile deployment (see the case study: OPPO Physics Wallpaper). In addition, the Taichi compiler automatically optimizes the generated code, enabling efficient GPU computing on mobile devices.

Here, we use Instant NGP as an example to demonstrate the performance and results of Taichi NeRF deployment on mobile devices.

At present, we have successfully deployed NeRF on iPhone, iPad, and Android smartphones, achieving real-time interaction on iOS devices.

| Performance | iPad Pro (M1) | iPhone 14 |

|---|---|---|

| Instant NGP | 22.4 fps | 13.5 fps |

By using more deployment-friendly models (based on Octree, Spherical Harmonics, etc.), targeted model iterations, and optimizing the demo, we can further enhance the deployment performance. This means that Taichi still has a lot of potential to be explored in NeRF deployment on mobile devices. We welcome partners who are interested in different application deployment scenarios to contact us and jointly explore the unlimited possibilities of NeRF.

Conclusion

In the first part of the Taichi NeRF series, we introduced the basic concepts of NeRF, performance optimization, training, and deployment. As a differentiable renderer, NeRF has many other uses besides novel view synthesis. In the upcoming articles, we will bring you more exciting content, so stay tuned!

If you are interested in NeRF, feel free to join our discord channel. For partners interested in mobile NeRF training and deployment, please contact us at contact@taichi.graphics.